“Books are a fantasy-oriented way to learn basic truths,” beloved children’s book author and illustrator Tomie dePaola said. “Truths, not morals. I avoid moralizing at all costs.”

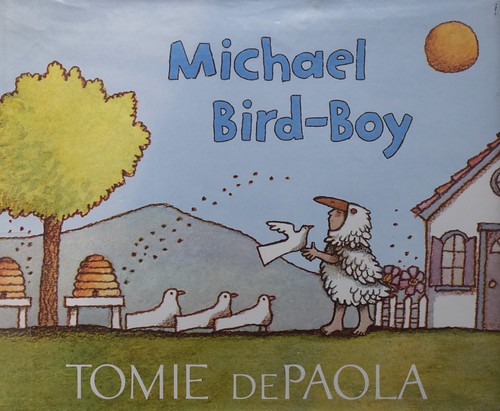

His ability to point out right from wrong without sliding into moral superiority is at the heart of the picture book “Michael Bird-Boy,” which examines environmental responsibility, an issue that’s grown in import since the book’s publishing 44 years ago.

Our generation, and especially those of us living in affluent nations, are in a position to pass on most of the burden of climate change to the global poor, future generations, and nonhuman nature. It is what philosophy professor Stephen M. Gardiner calls a perfect moral storm. And it is why the 84-year-old dePaola’s deft handling of where to place blame remains relevant.

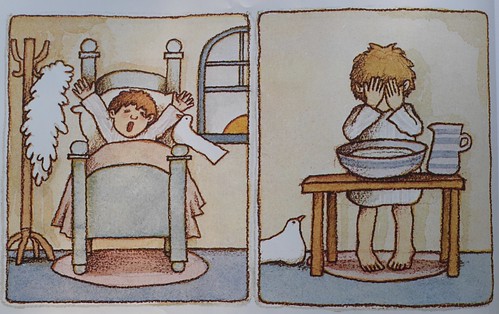

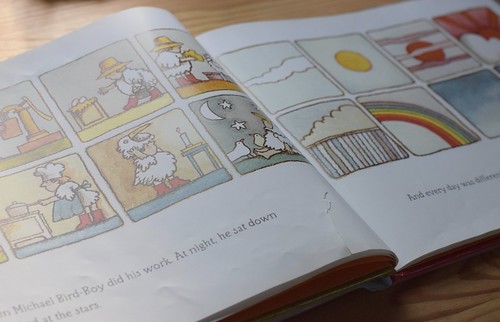

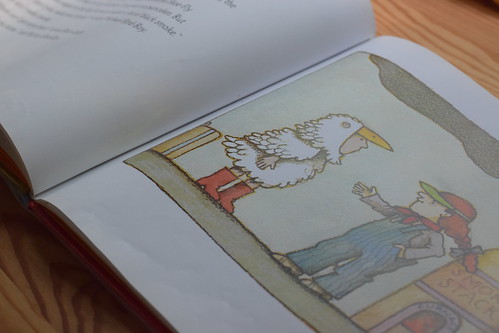

Michael Bird-Boy is a serious young man who wears a white feathery outfit and headdress (complete with beak). He takes care of a small farm, enjoying his routines and the diversity within them.

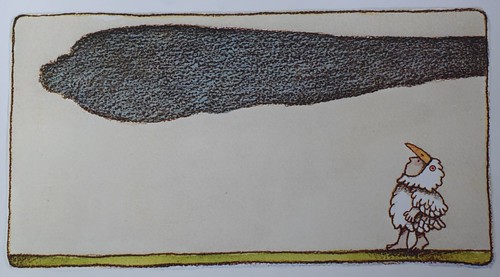

Each day is unique and beautiful, until a black cloud blocks the moon and the stars, sickens the animals, and wilts the flowers.

Michael Bird-Boy decides to investigate. He travels over a mountain, across water, and into the city where he discovers the source of the pollution: the Genuine Shoe-Fly Artificial Honey Syrup factory’s belching smokestack. Michael Bird-Boy doesn’t tell the factory owner, Boss-Lady, that she’s wrong to pollute. Instead, he points out the harm caused, and asks a question:

“Your factory is making the countryside very dark and dirty. … Why don’t you make real honey? Bees don’t make smoke.”

“Where can I get some bees?” asked Boss-Lady.

“I’ll send you some,” said Michael Bird-Boy.

He returns to the country and boxes up bees for Boss-Lady, who begins making real honey. For a while, things are good. Michael Bird-Boy’s animals are healthy and clean again, his flowers perk up, and he can see the stars and moon once more.

But a phone call from Boss-Lady forces Michael Bird-Boy to return to the city to help her figure out why the bees aren’t producing honey.

“Where are the flowers?” he asked.

“Flowers?” said Boss-Lady.

“Bees need flowers and hives,” Michael Bird-Boy said. And he drew a picture to show Boss-Lady how bees make honey.

“No wonder no honey,” said Boss-Lady. “Thanks again, Mike.”

A few weeks later, Boss-Lady writes Michael Bird-Boy a letter telling him all’s well, and she wants to thank him with jars of honey. “The bees are happy and so am I,” she wrote. “And there’s plenty of honey.”

Michael Bird-Boy bakes a cake with Boss-Lady’s honey, and the two have a party that ends with a star-studded evening and comet show.

“Michael Bird-Boy” was first published in 1975, and its story mirrors the triumphs of a decade that celebrated the first Earth Day, banned the toxic chemical DDT, regulated other pesticides, ensured cleaner drinking water from our taps, preserved marine habitat and waterways, protected endangered species, and brought global cooperation to fight the trafficking of endangered animal parts.

Its hopeful message that personal action can bring about great (global) change is much-needed given today’s threat of climate disruption. And its avoidance of preaching as it assigns environmental accountability is a path we might follow as we confront the injustice that those who are least to blame for carbon emissions are at greatest risk. Because the moral conundrum as to whether or not I should bother answering for my actions in the face of grand-scale catastrophe is a real one.

“It has sometimes been claimed (usually without evidence) that the harm caused by an individual’s participation in a greenhouse-gas-intensive economy is negligible,” said philosophy professor John Nolt, who in 2011 attempted to estimate the harm done by an average American. “This estimate is crude, and further refinements are surely needed. But the upshot is that the average American is responsible, through his/her greenhouse gas emissions, for the suffering and/or deaths of one or two future people.”

“Michael Bird-Boy” is a fantasy that rings with the truth that individuals, working together, can avoid great harm. The decision to not pit Michael Bird-Boy against Boss-Lady allowed them to discover where their interests intersected. Freed from judgment, Boss-Lady moved from environmental responsibility to individual accountability. The environment was restored, the factory was successful, and a lasting friendship formed.

- “Michael Bird-Boy” (public library).

- Tomie dePaola blog.

- 49 environmental victories since the first Earth Day (2019)National Geographic.

- Ethics and Global Climate Change (2012) by Stephen M. Gardiner and Lauren Hartzell-Nichols of University of Washington.

- How Harmful Are the Average American’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions? (2011) by John Nolt of University Tennessee.

Leave a Reply